This is the first in a three-part series examining a fresh approach to digital remittances in Indonesia.

By Angela Ang, Elwyn Panggabean, and Ker Thao

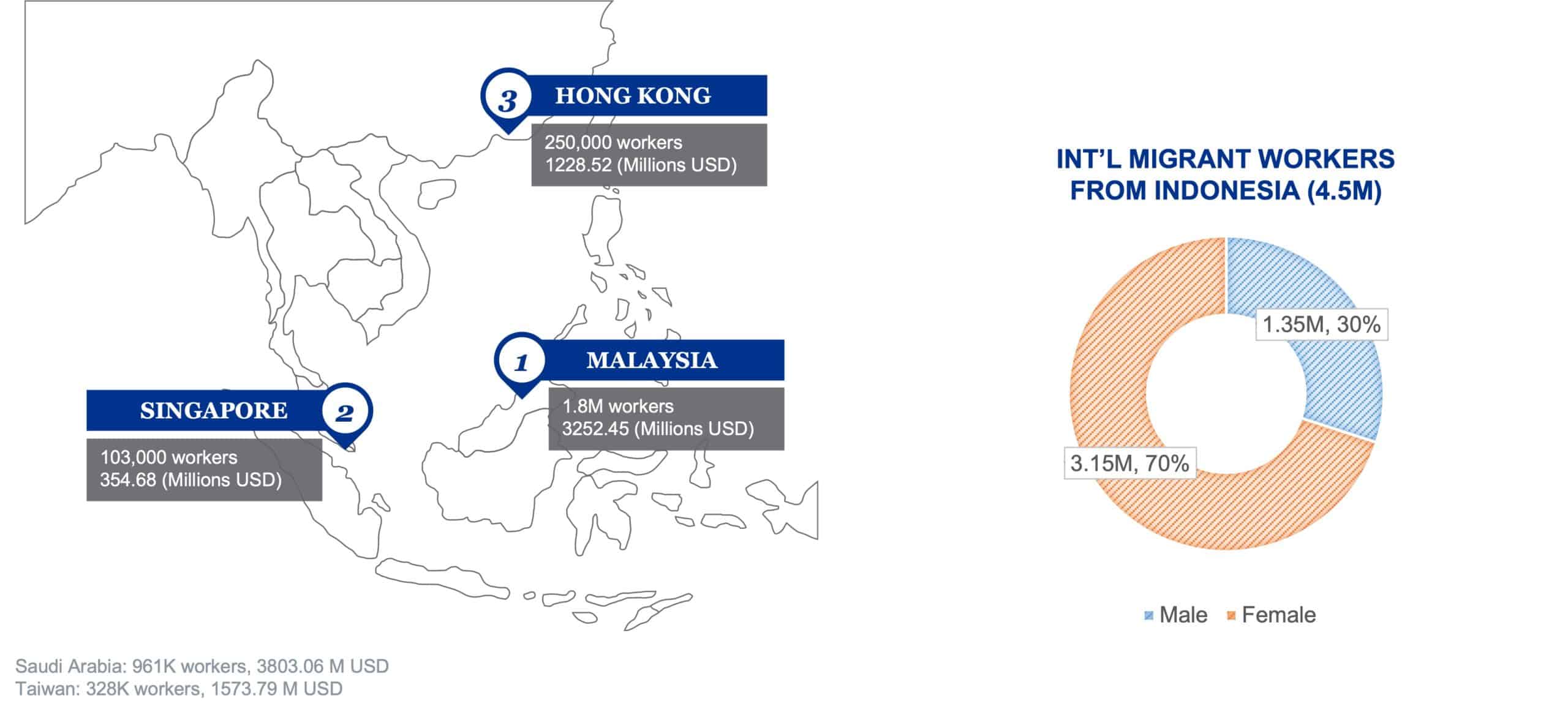

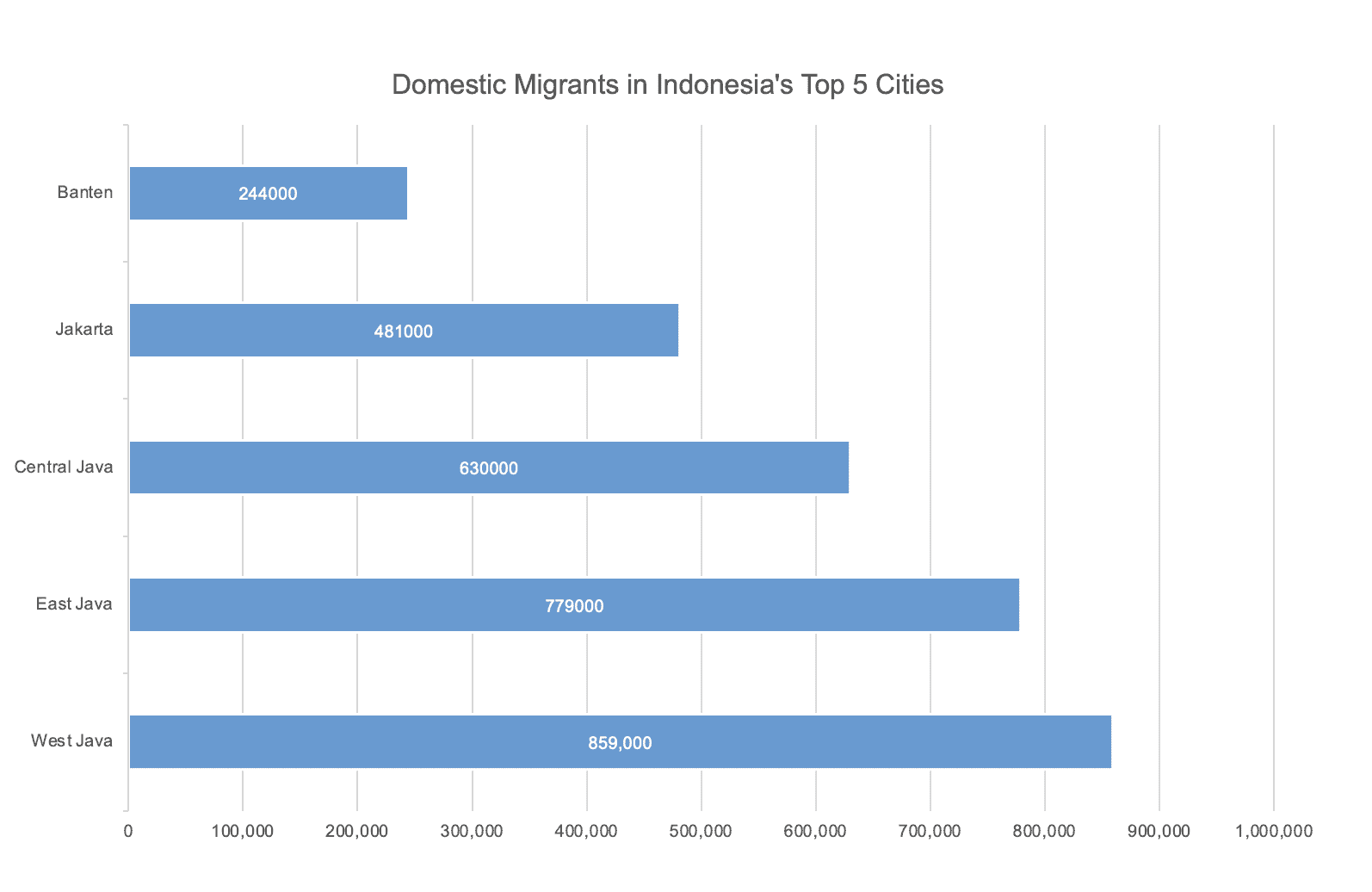

In Asia, Indonesia has the second largest migrant population, with international migrant workers comprising a large portion of the economy. There are approximately 4.5 million international migrant workers, of which almost 3 million (70 %) are women and the majority are employed in domestic services. Indonesia also has an additional 4.2 million domestic migrant workers (approximately 68% women) who are employed as factory workers, babysitters, housemaids, and caretakers. Many of these migrant workers rely heavily on informal channels to fulfill their remittance needs to send money home to family, but, due to limited or difficult to access affordable remittance services, face high service fees and the risk of theft and loss.

In recent years, Indonesia’s financial sector has been quickly evolving and continues to become more dynamic, with new non-bank players slowly emerging as critical contributors to financial inclusion. The Financial Inclusion Insight Survey 2020 shows that, in Indonesia, there has been a significant 2.5x increase in e-money users and an overall 19.5 percent increase in user awareness from 2018 to 2020. The rapid growth of smartphone ownership in Indonesia, compared to basic and feature phones, holds great promise for e-money to help advance financial inclusion for low-income women, particularly as mobile phones are key to driving digital payments and the increased use of server-based e-money and mobile banking.

While the rise in smartphone ownership is encouraging, progress has not been accompanied by equitable opportunities for various low-income populations, such as women migrant workers. According to GSMA’s Mobile Gender Gap Report, the mobile phone ownership gender gap still remains the same for women across low and middle-income countries. Many migrant workers in Indonesia also come from rural and remote parts of the country, where smartphone ownership and adoption of digital services is slow to materialize.

Women’s World Banking sees an opportunity to engage with women migrant workers and bring them into the formal financial sector by increasing their awareness and adoption of digital financial services—starting with a digital remittance service that is reliable, trustworthy, and cost-effective. To this end, we have partnered with DANA, one of the largest e-wallet providers in Indonesia, to develop solutions that can offer and drive the use of affordable and safe remittance services through an e-wallet for women migrant workers.

Through leveraging the advanced technology embedded in DANA, both Women’s World Banking and DANA hope to create greater economic stability and prosperity for women, families, and their communities. Furthermore, instilling a perception that digital wallets can be easily used by anyone—including international and domestic migrant workers—to support their family’s livelihood in their hometown, safely and conveniently.

About the migrants: Insights from our field research

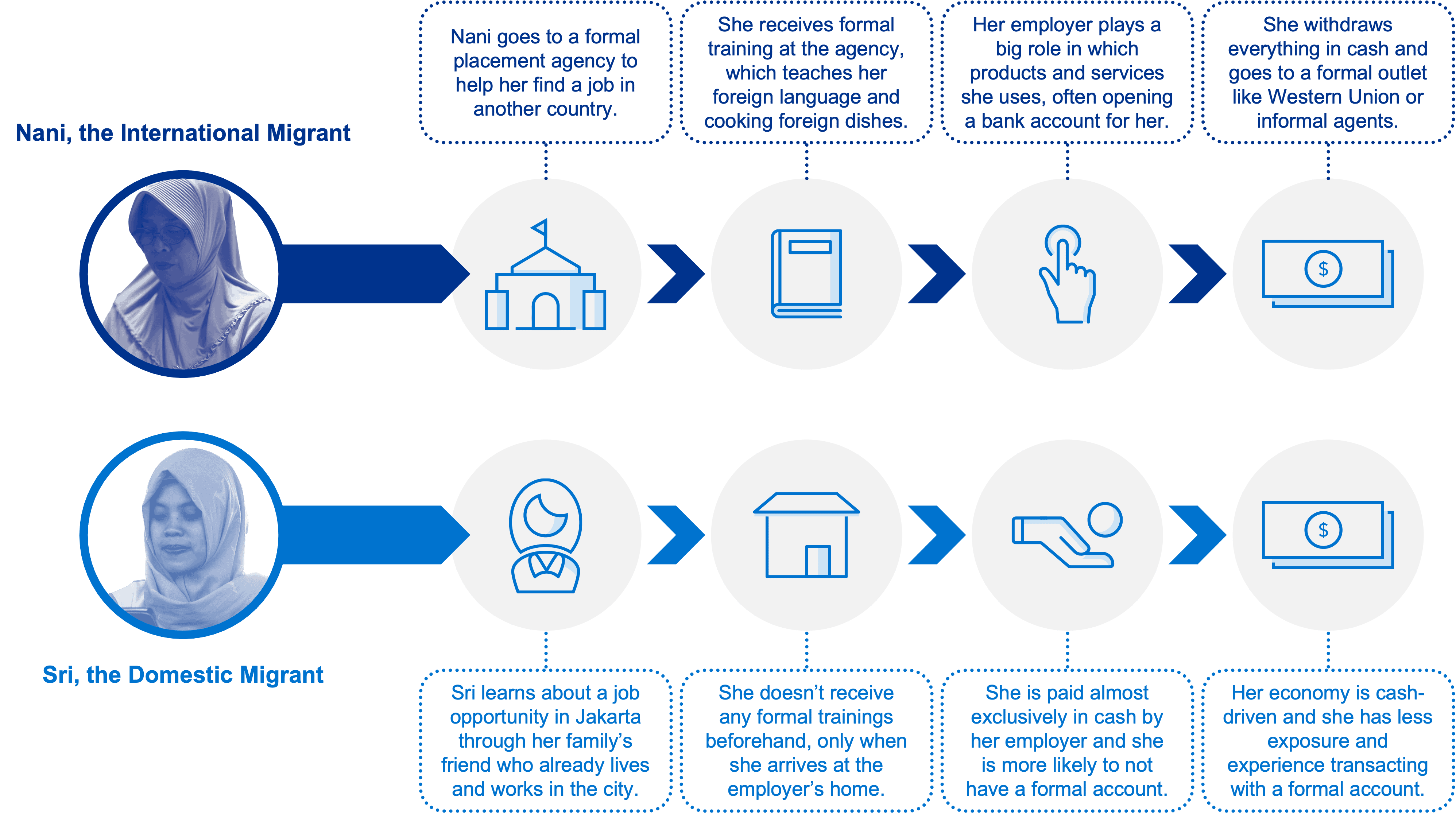

The respective journeys of international and domestic migrant workers in Indonesia vary significantly from one other, the primary differentiator being the formality of their employment processes. International workers are more likely to go through formal placement agencies, whereas domestic migrant workers rely on informal sources for their employment, often referrals from other migrant family or friends. While actual retention for migrant workers varies greatly, the majority of workers find employment in the domestic service sector (e.g., household helpers, caretakers, babysitters, cooking, and cleaning).

The International Migrant Worker

Once abroad, international migrants rely largely on their employers and a small migrant community, made up of existing colleagues, friends, and family members in the destination country, as trusted sources of information. As a result, many migrants opt into using products and services that are referred to them by these trusted individuals. Employers also play a crucial role by influencing which financial products and services migrant workers use and often prefer to pay their workers through formal bank accounts. As a result, many international migrant workers are more likely to have access to a formal bank account.

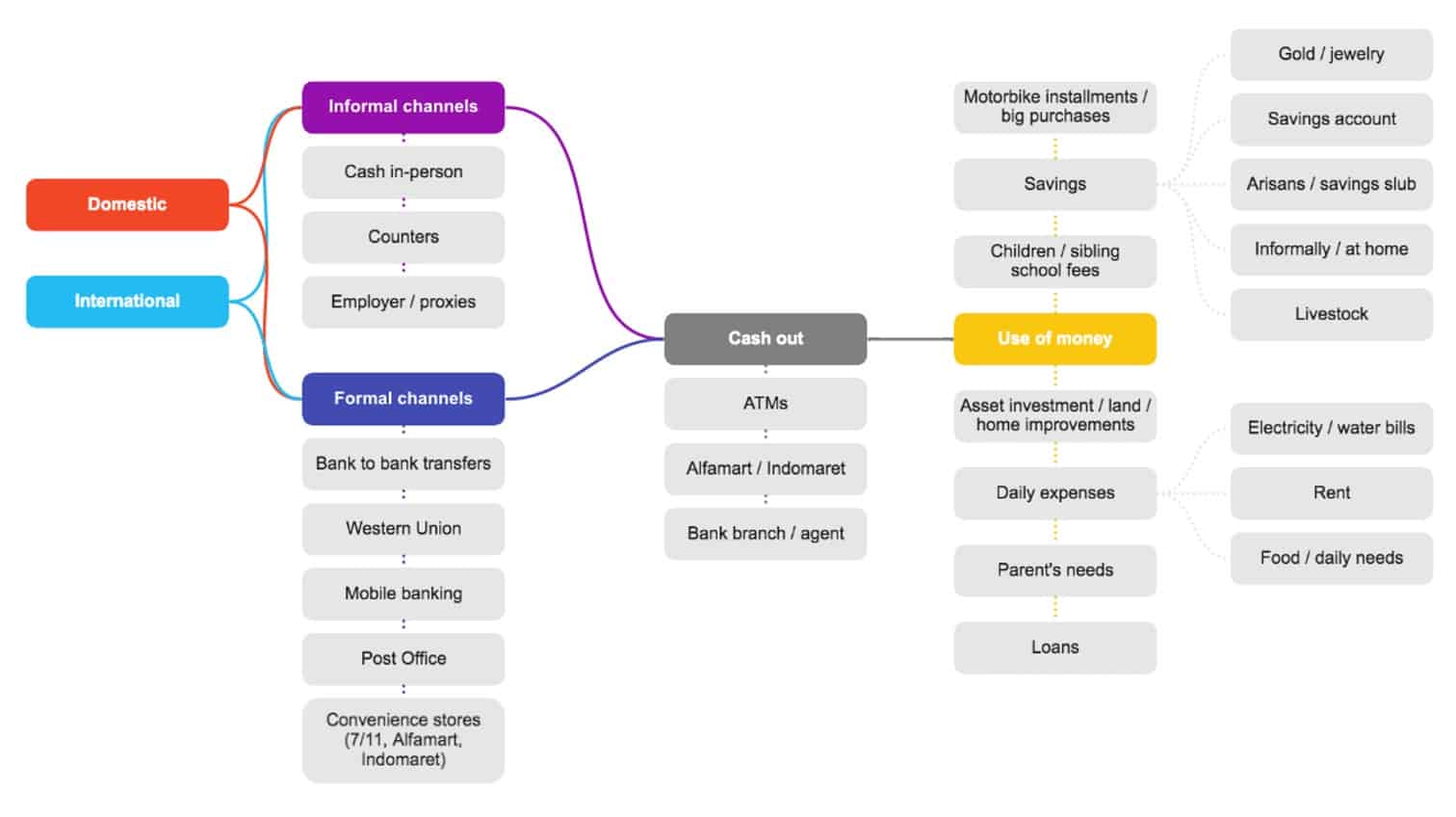

Unfortunately, access does not always translate into usage. While many international migrant workers have access to bank accounts, they do not necessarily use the account to send money back home. Rather, they will still withdraw all their funds and send cash through a formal outlet like Western Union or merchants (e.g., Indonesian shops), which act as informal money transfer agents between communities and countries. Sending remittances is also only half the story; the other half is making sure that money sent is accessible by recipients. Many recipient families do not have bank accounts, and therefore, migrant workers will send money to a relative’s or neighbor’s account, which can be easily cashed out at nearby agents, bank branches, and ATMs.

Case Study A: Nani, The International Migrant Worker

Nani is a 36-year-old migrant worker in Hong Kong, working as live-in house help who cooks, cleans, and takes care of her employer’s family. She comes from a small village in rural Indonesia, where her parents are taking care of her three children. She found her job through the help of a formal placement agency, which helped train her by providing basic language classes, housekeeping training, and cooking international dishes. Although it was a hard decision at first, she moved abroad for bigger and better opportunities to earn more money to support her family.

Nani is not very technologically literate, but she understands how to use social media to stay connected with her family and communicate with her employer, colleagues, and friends. Due to her limited technological awareness and knowledge, she relies on her employer’s advice on what to use. As a result, her employer has opened a bank account for her, where she receives her monthly salary.

Each time she receives her salary, Nani goes out during her limited free time to send money to her family. For convenience, Nani prefers to do all of her errands in a central location and chooses a nearby remittance service that guarantees delivery of her funds but requires a higher transaction fee.

The Domestic Migrant Worker

Similarly, domestic migrant workers depend on their small migrant community in the city they live or work to understand what financial products and services to use. Unlike their counterparts, domestic migrant workers are less likely to have access to a formal bank account and are paid almost exclusively in cash by employers. In a cash-driven economy and environment, domestic migrant workers lack valuable experience in using a bank account and thus have concerns about making mistakes when using unfamiliar products and services.

The lack of access, exposure, and experience with formal financial products and services contributes directly to why many domestic migrant workers choose informal methods for remittances. From their perspective, it is much easier and simpler to have their employers send money home for them and to use someone else’s account than to go through the trouble of establishing and maintaining one of their own. A similar logic can be seen when domestic migrant workers actually select where and to whom they send money; typically, money (50-70% of their entire salary) is sent to whoever has or owns an account back home, whether a parent, neighbor, or friend, so long as funds can be converted to cash and received by the intended recipient.

Case Study B: Sri, The Domestic Migrant Worker

Sri is a 2

Sri has a smartphone and uses it primarily to stay connected with her family and friends back home, but she has limited data and internet connectivity. With very low memory on her phone, Sri carefully chooses which mobile apps she keeps and uses and which she deletes. Although she has low e-money awareness, she has heard about some apps, such as OVO and GoPay.

Since Sri does not have a bank account, she relies on her employer to send 50-70% of her salary home or uses her family or friend’s bank account when sending money home. Whatever is left of her salary, she spends on her daily expenses and saves in her room or on her person.

What can we do to offer an affordable and safe remittance service for women migrant workers?

Based on this research, remittances for both international and domestic migrants use up most of their salaries, leaving only enough for their daily needs and expenses. Migrants often speak with recipients on how to use the money, which typically covers a variety of expenses and the needs of families back home. After all primary expenses have been paid for, the remaining funds are used for savings, as an investment for the family’s future. In the event of larger purchases, such as a motorbike, the money is used to cover substantial payment installments. Other funds may go towards home improvements and land purchases as investments for the future.

Because migrants’ salaries are the main way of supporting their families’ livelihoods, migrant workers highly value the secure and guaranteed delivery of their funds. When choosing a specific remittance service, not only will migrants opt for one that is costly but guarantees the safe and timely delivery of funds, they will also choose one that is easily accessible for the recipients back home. Therefore, when selecting a remittance service, migrant workers often have to consider multiple factors that could impact them as economic providers (the senders), in addition to their beneficiaries (the recipients).

Clearly, there is a need for a remittance service that resonates with women migrant workers—one that is designed to be fast and easy, ensure safe delivery of funds, and be easily accessible for recipients. By understanding the migrant’s needs, behaviors, and concerns, and what they value most in remittance services, Women’s World Banking will be better positioned to successfully help migrant workers in Indonesia adopt and readily use digital remittance services that work in their specific context.

In Part 2, we will share our specially designed solution that targets migrant workers and promotes the use of digital formal financial services to fulfill their remittance needs.

Women’s World Banking’s work with DANA Indonesia is supported by The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.