By Nithya Sharma (Women’s World Banking); Carolanne Boughton, and Sasha Polikarpova (Baringa)

The impact of climate change is reverberating around the world, with increasing frequency and severity of weather events, rising temperatures, and loss of biodiversity. While multilateral governance bodies including the United Nations emphasize that the world’s wealthiest countries, companies, and individuals[1] drive climate change, its harmful effects are disproportionately felt by the world’s most vulnerable, particularly low-income women, exacerbating existing economic, health, social and environmental disparities.[2]

Access to financial solutions is critical to enabling low-income women to build resilience against economic shocks related to climate change and adapt to the effects of climate change on their economic lives. However, globally, low-income women face unique barriers to accessing financial solutions and often lack access to these safety nets during times of crises, exacerbating the impact of such events on their lives.

Financial service providers (FSPs) have a critical role in designing and developing these solutions to support low-income women’s security, prosperity, and economic empowerment. To do so effectively, financial institutions must embed climate risk preparedness into their core business operations to reduce their own risks to the impact of climate risk and better respond to market needs and take advantage of new opportunities to increase the financial inclusion of low-income women.

Women’s World Banking has partnered with Baringa to analyze the interconnections of gender, financial inclusion, and climate change. We conducted a workshop in June to educate financial service providers on embedding climate risk assessment into their institutions (view the recording of this event). This blog post shared the key insights from this workshop.

Climate change has a disproportionate economic impact on low-income women

Climate change has worsened economic inequality between developed and developing nations by 25% since 1960, and the effects of climate change could reduce global GDP by 11-14% by 2050, or $23 trillion in economic output, with the most significant impact felt in South and Southeast Asia.[3,4]

Low-income women are acutely vulnerable[5] to the economic impacts of climate change, including both sudden extreme weather events and longer-term climate impacts. Pre-existing gender inequalities exacerbate the economic impacts of climate change for low-income women, including:

Overrepresentation in lower income communities. Of the 1.3 billion people living in poverty, nearly 70% are women.[6] Low-income segments are more likely to be pushed into poverty because of a single economic shock (e.g., from climate event). In fact, new research shows that 132 million additional people could be pushed below the poverty line by 2030 because of climate change[7], driven by rising food prices, health shocks, and natural disasters.

Overrepresentation in sectors of the economy highly vulnerable to climate change. Women represent 60% of agricultural sector employment in low-income countries[8], a sector demonstrably affected by shifting precipitation patterns, increased temperatures, and extreme weather events. Often tied to agriculture, women also make up most the world’s informal sector workers, with little to no financial security and stability to build resilience to economic shocks from climate change.

Limited decision-making power in their households, worsened by restrictive social norms and legal barriers. Gendered roles within households can exclude women from decision-making processes, limiting women’s ability to take actions on behalf of their family to combat the economic effects of climate change. Legal and social norms further entrench women’s differentiated access to resources. For example, even though women are the primary producers of food, they own less than 10% of the agriculture land.[9]

Being on the “frontlines” of environmental challenges. Women are often responsible for essential, unpaid, household work such as food production, water collection and other labors dependent on the environment. As the effects of climate change increase, these tasks will require more effort (e.g., need to travel farther distances for resources) or become more dangerous (e.g., compromised sanitation after floods or droughts). These challenges have upstream effects in limiting girls’ access to education and economic opportunities as they may be required to contribute to household activities, as well as downstream implications on the health, safety and economic security of women and their families.

Increased vulnerability when displaced due to climate change. The world is already seeing climate change refugees and estimates suggest 1.2 billion could be displaced globally by 2050 due to climate stressors.[10] The majority (80%) of those displaced by climate-related disasters are women and girls[11], who face gender-specific challenges, including separation from support networks, increased risk of gender-based violence, and reduced access to employment, education, and essential health services, including sexual and reproductive health-care services, and psychosocial support.

Financial inclusion accelerates women’s economic empowerment and mitigates the economic impacts of climate change – and must be driven by financial service providers

Accessible and relevant financial solutions are critical to enabling vulnerable populations to build resilience to the economic shocks of climate change. Financial service providers can lead the creation of these solutions and drive responsible market implementation.

Insurance – Access to insurance can provide economic security and help low-income women mitigate climate-related threats. Health insurance provides women with the means to meet healthcare costs for climate-related health impacts, increasing the likelihood that women will seek medical care during disaster risk recovery. Accessible and affordable crop insurance or weather-index insurance will allow smallholder farmers (many of whom are women) to prepare for catastrophic climate events and increase economic productivity.

Savings – Savings can provide low-income women with a designated safety net to help adapt to the economic impacts of climate change and support disaster risk recovery after catastrophic events. Furthermore, low-income women often save informally and in physical assets (e.g., livestock), which could face threats from climate change, and access to formal savings mitigates these risks and ensures continued access to financial resources even in times of crisis.

Credit – Access to flexible credit products can help low-income women, particularly small business owners, increase investments in new, clean technologies and develop climate-resilient products to help mitigate and adapt to the economic impacts of climate change (e.g., small-scale irrigation technology in areas with changing precipitation).

Payments and Remittances – Broad access to digital payments (including G2P transfers) and remittances ensure that low-income women have access to funds to both prepare for disaster risk relief prior to and during climate crises as well as support disaster risk recovery after climate crises take place. However, access to technology and building trust will be critical to ensure widespread adoption of such solutions by low-income women.

Financial service providers have a critical role to play in supporting adaptation and mitigation of the economic impacts of climate change – particularly those faced by low-income women

The financial sector and the financial inclusion community has a critical role in developing solutions to mitigate the economic impact of climate change as well as supporting low-income women’s adaptations to climate realities.[12] Financial service providers must understand how climate change will impact the risk profile of companies in emerging markets, including those owned by low-income women. In the last decade, investors, customers, and governments have been increasingly calling on and at times mandating financial services providers to address climate change risks and allocate more capital to finance a low carbon economy.

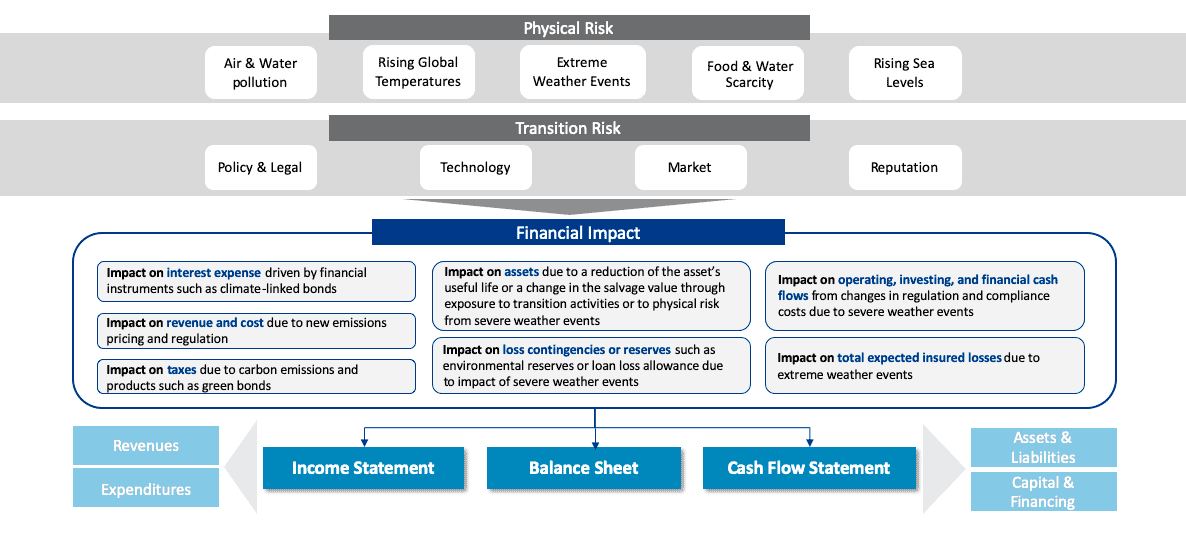

To mitigate the economic risk that climate change poses and facilitate a just transition for women and disadvantaged populations, companies must first understand the types of climate change risk and their impacts on their business, strategy, and financial planning. Climate risks for financial companies are broken into two broad categories: physical and transition risk with direct financial impact to the institution – highlighted in the table below. Understanding the implications of climate change risks and translating it into financial impacts can be helpful in prioritizing actions to mitigate risks across the business.

How to build internal climate risk preparedness

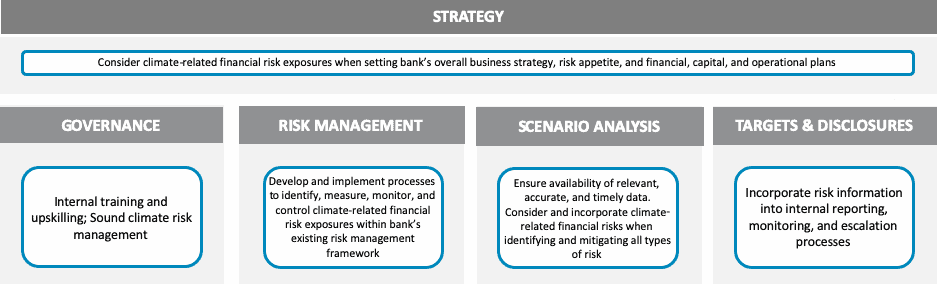

So, it’s clear financial institutions need to respond to climate risk – both to reduce their own risk and to play a vital role in mitigating the impacts of climate change, including on low-income women. But how do you build internal climate risk preparedness? At Baringa, we are working with prominent US and global financial institutions to do this, defining climate risk targets for embedding climate change into their existing risk organization, and supporting clients to align with industry best practice as well as regulatory expectations.

There is a comprehensive set of frameworks and tools that can help financial institutions create robust processes for climate risk identification, assessment, and management. Ultimately, climate risk management should be embedded into existing risk management activities and consider all aspects of the business.

Given its drastic impact, climate risk should be considered a priority for financial institutions and must be reviewed at the highest levels of an organization – the board. To properly assess and adjust business strategies to integrate climate risk, the board should be trained to understand climate risk and its implications. Strengthening climate expertise will help the board establish appropriate mandates for senior management and monitor progress against objectives and targets.

Proper governance, organizational buy-in and oversight facilitates climate risk embedding into risk management frameworks

For financial services institutions, climate risk should be categorized in the context of traditional industry risk types and categories (e.g., credit risk, market risk, operational risk, etc.). Additionally, financial institutions should consider the materiality of climate-related risks across various time horizons – short, medium, and long-terms. This categorization will assist financial institutions in implementing processes for managing identified risks.

The one prominent challenge organizations face in accurately assessing climate-related risks is uncertainty of how presently identified risks will evolve in the future, and how these changes will impact businesses, strategies, and financial performance in the medium and long-term. To help tackle this challenge, financial institutions can utilize climate change scenario analysis – a forward-looking tool that can help illuminate future exposure to both transition and physical climate-related risks. There is a wide variety of scenario analysis models available on the market, offering both qualitative and quantitative outputs particular to a range of business needs. The scope of an organization’s scenario analysis’ activities will depend on an its needs, regulatory mandates, capabilities, and ambition, and can evolve over time.

Once an institution has identified its climate-related risks, and established proper governance and oversight, it should consider setting targets to address its climate-related risks. To mitigate global climate impacts and reduce climate risks, financial institutions are setting Scope 3 GHG emissions reduction targets aimed at aligning their financed emissions with a net zero scenario by 2050. Regardless of the metric chosen, financial institutions must ensure that targets are quantifiable, relevant to its climate-related risks and strategy, and that the chosen targets are tracked and disclosed continuously. Implementing this robust and comprehensive climate risk embedding framework will not allow create a more resilient internal operating model but encourages market participation in addressing both the risks and opportunities of climate change. This could take the form of new financial products aimed at funding social and environmental projects in emerging markets or helping carbon-intensive industries transition to the new economy. Overall, climate risk management asks an organization to consider the impact it has on its direct community, and the communities up and down its supply chain. Taking on this accountability will lead to a more inclusive, responsible, and just financial system for the world’s most vulnerable – notably low-income women.

Low-income women[13] not only bear the burden of social and economic consequences of climate change, but also bring unique knowledge and experience that is critical to the development and implementation of financial solutions

The voices of women and girls are integral to ensuring solutions that consider their needs and preferences and are most effective in mitigating and adapting to the economic impacts of climate change.

Increasing the representation of women in the decision-making process positively impact the likelihood of developing meaningful solutions and transitioning to a more climate-resilient and gender-just economy. At the systemic level, increasing female representation in national parliaments leads to the adoption of more stringent climate policies and results in lower emissions.[14] At the corporate level, representation of women on corporate boards and in leadership roles is associated with increased transparency around climate impact and positively correlates with more transparency and communication of climate impact information.[15] Finally, expanding equal access to resources can increase productivity and mitigate the impacts of climate change – for example, providing women smallholder farmers with equal access to resources increasing farm yields by nearly 20-30%, reducing food insecurity for nearly 100 to 150 million people.[16]

To promote a more gender-just transition and ensure financial institutions are designing more inclusive financial solutions, climate change risk assessment must be embedded into the broader Climate Risk and ESG agendas of financial institutions. Companies must actively advocate for women’s economic and financial inclusion through public policy engagement and must be held accountable to driving change and developing a holistic assessment of climate risk that provides a strategic advantage for financial institutions to become leaders among peers and promote a more inclusive, equitable, and profitable financial system. Financial institutions can leverage the data, analytics, and processes of a strong climate risk management framework to further raise awareness and inclusion of women in the energy transition. These institutions should play a role in educating their customers, particularly those who have been historically excluded from financial services, on the risks and opportunities that climate change poses. Promoting the access and knowledge of these communities will foster a more resilient and just economic system for both low-income women and financial service providers.

About Women’s World Banking: Empowering Women Through Financial Inclusion – Women’s World Banking is dedicated to driving financial inclusion to economically empower the nearly 1BN women in the world with limited or no access to formal financial services. Using our sophisticated market and consumer research and women-centered design approach, we turn insights into meaningful action to design and advocate for digital financial solutions, policy engagement, leadership programs, and gender lens investing in order to build a world where every woman has the power to participate in and benefit from economic growth, achieving prosperity, stability and dignity.

Find out more at www.womensworldbanking.org or get in touch at communications@womensworldbanking.org

Overview of Baringa’s capabilities

Baringa is building the world’s most trusted consulting firm – creating lasting impact for clients and pioneering a positive, people-first way of working. We work with everyone from FTSE 100 names to bright new start-ups, in every sector. We have hubs in Europe, the US, Asia and Australia, and we can work all around the world – from a wind farm in Wyoming to a boardroom in Berlin.

As a global leader on the energy transition, we’re helping financial institutions to understand, measure, and act on their environmental and social impact. And as a Certified B Corporation®, we’ve proven that we too have built social and environmental good into every bit of what we do.

Find out more at baringa.com or get in touch with Hortense.Viard-Guerin@baringa.com.

[1] (UNEP, UNEP Copenhagen Climate Center (UNEP-CCC), 2020). The UN 2020 Emissions Gap Report states the combined emissions of the richest one percent (those with net assets of $871,320 USD or more) of the global population account for more than twice those of the poorest 50% do.

[2] Invalid source specified.

[3] (Garthwaite, 2019)

[4] (SwissRe Institute, April, 2021)

[5] Vulnerability is a multidimensional social process in which women experience social, political, and economic barriers

[6] (Osman-Elasha, n.d.)

[7] (Jafino, Walsh, Rozenberg, & Hallegatte, 2020)

[8] (The World Bank, 2022)

[9] (Osman-Elasha, n.d.)

[10] (Institute for Economics & Peace, 2020)

[11] (United Nations, 2021)

[12] See, for example, work coming from the Alliance for Financial Inclusion, the Office of HM Queen Maxima at UNSGSA, the Center for Financial Inclusion at Accion, the World Bank, and others.

[13] It is crucial that an intersectional approach be taken in all governance, funding and solutions actions, recognizing that women are not a homogenous group, but instead gender identities are closely intertwined with class, ability, race, ethnicity, age and other historically marginalized social identities

[14] (UN Women, 2022)

[15] (UN Women, 2022)

[16] (UN Women, 2022)